Warbaby

One Too Many

- Messages

- 1,549

- Location

- The Wilds of Vancouver Island

This interesting article on the naming of hats was on today's edition of the World Wide Words email list.

WORLD WIDE WORDS ISSUE 741 Saturday 18 June 2011

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Author/editor: Michael Quinion US advisory editor: Julane Marx

Website: http://www.worldwidewords.org ISSN 1470-1448

-------------------------------------------------------------------

"Because of declining sales, in 1965 the British Hat Council felt it

necessary to create an advertising slogan, "get ahead, get a hat".

Earlier generations would have found the advice otiose, since only

the meanest members of society went about without one. Photographs

from the early to middle twentieth century immediately strike us

because of all the hats, whether it's a sea of flat caps at a

football match, a horde of be-bowlered city clerks crossing London

Bridge on their way to work, a group of heavily-hatted women

enjoying a walk in the park, or any man in an old black-and-white

film, whose head is invariably topped off with a Homburg, trilby,

fedora, or other style.

The soft hat called a Homburg came from the exclusive German spa

town of Bad Homburg near Frankfurt, often frequented by royalty in

late Victorian times. The hat became fashionable in London because

the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) regularly visited the town

from 1882 onwards, liked the style of the local hat and brought it

home with him (in 1893, advertisers in American newspapers were

calling it "the latest fad", though they spelt it "Homberg"). The

name was also early on confusingly given to a woman's hat of rather

different style that was also known as the Brighton hat:

The woman who started the fashion of the Brighton or

Homburg hat has much to answer for. She has robbed

thousands of Englishwomen of their character - so far as

character is represented by headgear. Had Dame Nature

foreseen the Homburg hat craze she would not doubt have

been accommodating enough to construct all women's faces

after the same pattern with the oblong mask, classic

features, and shapely head required for the severity of

such a style of headgear.

[Manchester Times, 5 Jun. 1891.]

The male style could be variously black, grey or and brown. In the

1930s the black hat became known as the Anthony Eden, or the Eden

hat, after the then British Foreign Secretary, who commonly wore

one.

The other two of the three classic styles of men's headwear of the

period were popularised by actresses. The fedora, later to be the

classic topping of the Italian-American mobster, was named after

the title and main character in a famous play by the French

playwright Victorien Sardou, first performed in 1882 with Sarah

Bernhardt as the hat-wearing Russian princess Fédora Romanov. The

name of the trilby comes from a play adapted by the American Paul

Potter from a book by George du Maurier. The latter had been an

immense hit when it came out in 1894:

We are beset by a veritable epidemic of Trilby fads.

Trilby bonnets and gowns and shoes, Trilby accents of

speech and Trilby poses of person. Trilby tableaux, teas

and dances. Trilby ice cream and Trilby sermons, Trilby

clubs and reading classes and prize examinations, Trilby

nomenclature for everybody and everything.

[New York Tribune, Mar. 1895. A Trilby ice cream was

so called because it was moulded into the shape of the

hat.]

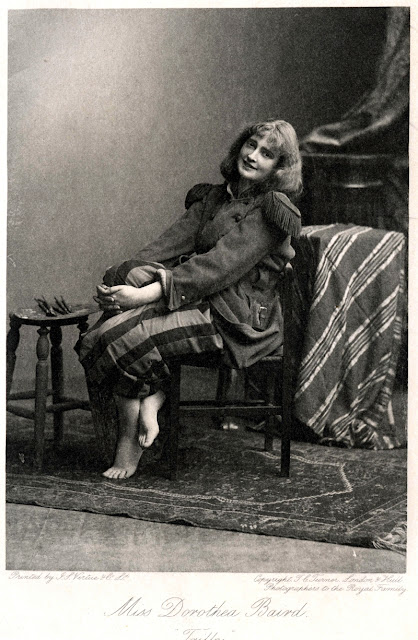

The play was brought to London in November 1895 by the impresario

Beerbohm Tree and was a huge success, ensuring that the hat worn by

the bare-footed, chain-smoking, 20-year-old leading lady Dorothea

Baird would become part of the British trilby craze. Her picture,

wearing that hat, appeared on postcards, in advertisements, on

chocolate boxes, and in newspapers.

Women's hats of the period also had names with literary links. The

Dolly Varden was large, with one side bent down, "abundantly

trimmed with flowers" as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it. The

name came from the coquettish character in Charles Dickens's

Barnaby Rudge, though her hat, as described by Dickens, was more

modest:

... a little straw hat trimmed with cherry-coloured

ribbons, and worn the merely trifle on one side - just

enough in short to make it the wickedest and most

provoking head-dress that ever malicious milliner

devised.

The sale of William Frith's portrait of Dolly Varden at the auction

of Dickens's effects in June 1870, shortly after the author's

death, stimulated a fashion in the UK and the US for the

eighteenth-century costume it portrayed, particularly among younger

and middle-class women. Such was Dolly's popularity that her name

was soon applied to a parasol, a racehorse, two American species of

fish, a mine in Nevada and a cake, as well as the hat. To judge

from these comments, however, the fashion was not universally

popular in America:

The maids of Athens, and the matrons too, do not take

to Dolly Vardens worth a cent.

[Athens Messenger (Ohio), 16 May 1872.]

Was ever any new costume more criticized than the new

"Dolly Varden"?

[Harper's Weekly, May 1872.]

Another a little later was the merry widow, an ornate and wide-

brimmed hat whose style and name derived from the hat worn by Lily

Elsie in the London premiere of Franz Lehar's operetta in June

1907. The show made Ms Elsie a star and the focus of a craze, just

as happened with Dorothea Baird a decade earlier. Her picture -

wearing that hat - appeared very widely in advertisements and

picture postcards. The style was as common in the US as in Britain,

resulting in this puzzled comment:

There you will see women wearing "Merry Widow" hats

who are not widows but spinsters, or married women whose

husbands are very much alive, and the hats in many cases

are as large as three feet in diameter.

[America Through the Spectacles of an Oriental

Diplomat, by Wu Tingfang, 1914.]

He was right about their size. Some American examples became so

large, in fact, that a picture postcard of the time featured a

wearer staring sadly at a sign:

Ladies with Merry Widow Hats Take Freight Elevator.

Another style, popularized by the Prince of Wales in 1896, was the

boater, a straw hat with a flat crown and brim, so named because it

became the usual informal wear when messing about in boats, but now

remembered by many people mostly as part of the official costume of

their local butcher, not least Corporal "They don't like it up 'em"

Jones of the BBC television series Dad's Army."

(continued in next post)

WORLD WIDE WORDS ISSUE 741 Saturday 18 June 2011

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Author/editor: Michael Quinion US advisory editor: Julane Marx

Website: http://www.worldwidewords.org ISSN 1470-1448

-------------------------------------------------------------------

"Because of declining sales, in 1965 the British Hat Council felt it

necessary to create an advertising slogan, "get ahead, get a hat".

Earlier generations would have found the advice otiose, since only

the meanest members of society went about without one. Photographs

from the early to middle twentieth century immediately strike us

because of all the hats, whether it's a sea of flat caps at a

football match, a horde of be-bowlered city clerks crossing London

Bridge on their way to work, a group of heavily-hatted women

enjoying a walk in the park, or any man in an old black-and-white

film, whose head is invariably topped off with a Homburg, trilby,

fedora, or other style.

The soft hat called a Homburg came from the exclusive German spa

town of Bad Homburg near Frankfurt, often frequented by royalty in

late Victorian times. The hat became fashionable in London because

the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) regularly visited the town

from 1882 onwards, liked the style of the local hat and brought it

home with him (in 1893, advertisers in American newspapers were

calling it "the latest fad", though they spelt it "Homberg"). The

name was also early on confusingly given to a woman's hat of rather

different style that was also known as the Brighton hat:

The woman who started the fashion of the Brighton or

Homburg hat has much to answer for. She has robbed

thousands of Englishwomen of their character - so far as

character is represented by headgear. Had Dame Nature

foreseen the Homburg hat craze she would not doubt have

been accommodating enough to construct all women's faces

after the same pattern with the oblong mask, classic

features, and shapely head required for the severity of

such a style of headgear.

[Manchester Times, 5 Jun. 1891.]

The male style could be variously black, grey or and brown. In the

1930s the black hat became known as the Anthony Eden, or the Eden

hat, after the then British Foreign Secretary, who commonly wore

one.

The other two of the three classic styles of men's headwear of the

period were popularised by actresses. The fedora, later to be the

classic topping of the Italian-American mobster, was named after

the title and main character in a famous play by the French

playwright Victorien Sardou, first performed in 1882 with Sarah

Bernhardt as the hat-wearing Russian princess Fédora Romanov. The

name of the trilby comes from a play adapted by the American Paul

Potter from a book by George du Maurier. The latter had been an

immense hit when it came out in 1894:

We are beset by a veritable epidemic of Trilby fads.

Trilby bonnets and gowns and shoes, Trilby accents of

speech and Trilby poses of person. Trilby tableaux, teas

and dances. Trilby ice cream and Trilby sermons, Trilby

clubs and reading classes and prize examinations, Trilby

nomenclature for everybody and everything.

[New York Tribune, Mar. 1895. A Trilby ice cream was

so called because it was moulded into the shape of the

hat.]

The play was brought to London in November 1895 by the impresario

Beerbohm Tree and was a huge success, ensuring that the hat worn by

the bare-footed, chain-smoking, 20-year-old leading lady Dorothea

Baird would become part of the British trilby craze. Her picture,

wearing that hat, appeared on postcards, in advertisements, on

chocolate boxes, and in newspapers.

Women's hats of the period also had names with literary links. The

Dolly Varden was large, with one side bent down, "abundantly

trimmed with flowers" as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it. The

name came from the coquettish character in Charles Dickens's

Barnaby Rudge, though her hat, as described by Dickens, was more

modest:

... a little straw hat trimmed with cherry-coloured

ribbons, and worn the merely trifle on one side - just

enough in short to make it the wickedest and most

provoking head-dress that ever malicious milliner

devised.

The sale of William Frith's portrait of Dolly Varden at the auction

of Dickens's effects in June 1870, shortly after the author's

death, stimulated a fashion in the UK and the US for the

eighteenth-century costume it portrayed, particularly among younger

and middle-class women. Such was Dolly's popularity that her name

was soon applied to a parasol, a racehorse, two American species of

fish, a mine in Nevada and a cake, as well as the hat. To judge

from these comments, however, the fashion was not universally

popular in America:

The maids of Athens, and the matrons too, do not take

to Dolly Vardens worth a cent.

[Athens Messenger (Ohio), 16 May 1872.]

Was ever any new costume more criticized than the new

"Dolly Varden"?

[Harper's Weekly, May 1872.]

Another a little later was the merry widow, an ornate and wide-

brimmed hat whose style and name derived from the hat worn by Lily

Elsie in the London premiere of Franz Lehar's operetta in June

1907. The show made Ms Elsie a star and the focus of a craze, just

as happened with Dorothea Baird a decade earlier. Her picture -

wearing that hat - appeared very widely in advertisements and

picture postcards. The style was as common in the US as in Britain,

resulting in this puzzled comment:

There you will see women wearing "Merry Widow" hats

who are not widows but spinsters, or married women whose

husbands are very much alive, and the hats in many cases

are as large as three feet in diameter.

[America Through the Spectacles of an Oriental

Diplomat, by Wu Tingfang, 1914.]

He was right about their size. Some American examples became so

large, in fact, that a picture postcard of the time featured a

wearer staring sadly at a sign:

Ladies with Merry Widow Hats Take Freight Elevator.

Another style, popularized by the Prince of Wales in 1896, was the

boater, a straw hat with a flat crown and brim, so named because it

became the usual informal wear when messing about in boats, but now

remembered by many people mostly as part of the official costume of

their local butcher, not least Corporal "They don't like it up 'em"

Jones of the BBC television series Dad's Army."

(continued in next post)

Last edited: