LizzieMaine

Bartender

- Messages

- 34,195

- Location

- Where The Tourists Meet The Sea

Each week we'll be posting the story of a Golden Era woman who stands out for her achievements, her notability, and her personality -- some of them you might know, some might be new to you, but all are worthy of your attention.

Our first honoree is a truly remarkable woman -- Ruth Harkness, a real-life combination of Myrna Loy and Indiana Jones.

Ruth Harkness was born in 1900 in a small town in Pennsylvania. An indpendent minded woman from earliest childhood, she had a flair for fashion and art that led her, by the late twenties, to a productive career as a Manhattan dress designer. Her husband, William Harkness, was a globe-trotting adventurer and explorer whose great goal in life was to capture the first living specimen of the elusive Giant Panda, an animal then little known to the western world. Unknown to Ruth, Bill Harkness developed throat cancer in the early 1930s, and while on an expedition to the mountains of Western China he took a turn for the worse in 1934 and died in a Shanghai hospital.

Bill's death threw a switch in Ruth Harkness's mind. Up until then she'd been satisified with the life of a New York socialite -- but with her husband's passing she became determined to see that his lifelong dream was accomplished, and with no background or experience in exploring, hunting, or woodcraft, she traveled to China herself in 1936 to carry on his work. She found that his partner had been embezzling expedition funds and rid herself of him immediately -- hiring instead a young Chinese explorer named Quentin Young to serve as her guide, and outfitting herself in cut-down, resewn clothing from Bill's wardrobe, she headed into the forests in search of a panda.

The expedition made its way thru the western mountains and camped in an area known to be panda country. Against Ruth's explicit instructions, members of the exploration party shot an adult panda for food -- and to her horror, she discovered that the animal was a mother, her newborn infant crying in a nearby hollow tree. With no other choice, she wrapped the baby panda in her jacket and carried it back to camp -- nursing it with canned milk from the expedition's provisions, until they made their way back to Shanghai. Thru the influence of one of Bill's old friends, an executive of Socony Oil, she was able to get export papers for the cub -- describing it as "one small dog" in the paperwork -- and sailed for San Francisco.

She arrived in late November to a wave of publicity. The panda -- named "Su Lin," or "a little bit of something very cute" -- became a sensation, and for several months lived with Harkness in a suite at the Algonquin Hotel in New York until she could figure out where it would be best cared for. The Brookfield Zoo in Chicago agreed to accept custody of the cub, and once Su was safely boarded, she returned to China for the purpose of finding another young panda to serve as Su's companion. She returned home with another young cub, "Mei Mei", in early 1938, and the two pandas became inseparable playmates -- until, tragically, Su suddenly died from an infection resulting from a stick caught in his throat.

Ruth Harkness was shattered by Su's death, and her life began to spiral into depression. She tried another expedition to China and captured a third panda -- but before she could bring the new cub home, she was suddenly horror-struck by the implications of what she was doing: panda-hunting had become a fad and pandas were being taken out of their habitat in bunches to meet the demand from American zoos. She returned the bear to the forest and set it free -- and swore she'd never capture another animal again.

Ruth Harkness lived another eight years after that, working as a travel writer, but her zest for life was gone. She fell victim to alcoholism, and died alone in a hotel bathroom in 1947. Among the few scant posessions in her suitcase at the time of her death was a copy of "The Lady and the Panda," the book she'd written about her life with Su Lin, published just days before his death.

\

\

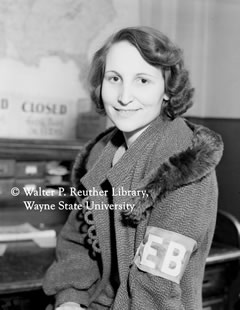

Ruth, Su Lin, and Mei Mei, February 1938.

Our first honoree is a truly remarkable woman -- Ruth Harkness, a real-life combination of Myrna Loy and Indiana Jones.

Ruth Harkness was born in 1900 in a small town in Pennsylvania. An indpendent minded woman from earliest childhood, she had a flair for fashion and art that led her, by the late twenties, to a productive career as a Manhattan dress designer. Her husband, William Harkness, was a globe-trotting adventurer and explorer whose great goal in life was to capture the first living specimen of the elusive Giant Panda, an animal then little known to the western world. Unknown to Ruth, Bill Harkness developed throat cancer in the early 1930s, and while on an expedition to the mountains of Western China he took a turn for the worse in 1934 and died in a Shanghai hospital.

Bill's death threw a switch in Ruth Harkness's mind. Up until then she'd been satisified with the life of a New York socialite -- but with her husband's passing she became determined to see that his lifelong dream was accomplished, and with no background or experience in exploring, hunting, or woodcraft, she traveled to China herself in 1936 to carry on his work. She found that his partner had been embezzling expedition funds and rid herself of him immediately -- hiring instead a young Chinese explorer named Quentin Young to serve as her guide, and outfitting herself in cut-down, resewn clothing from Bill's wardrobe, she headed into the forests in search of a panda.

The expedition made its way thru the western mountains and camped in an area known to be panda country. Against Ruth's explicit instructions, members of the exploration party shot an adult panda for food -- and to her horror, she discovered that the animal was a mother, her newborn infant crying in a nearby hollow tree. With no other choice, she wrapped the baby panda in her jacket and carried it back to camp -- nursing it with canned milk from the expedition's provisions, until they made their way back to Shanghai. Thru the influence of one of Bill's old friends, an executive of Socony Oil, she was able to get export papers for the cub -- describing it as "one small dog" in the paperwork -- and sailed for San Francisco.

She arrived in late November to a wave of publicity. The panda -- named "Su Lin," or "a little bit of something very cute" -- became a sensation, and for several months lived with Harkness in a suite at the Algonquin Hotel in New York until she could figure out where it would be best cared for. The Brookfield Zoo in Chicago agreed to accept custody of the cub, and once Su was safely boarded, she returned to China for the purpose of finding another young panda to serve as Su's companion. She returned home with another young cub, "Mei Mei", in early 1938, and the two pandas became inseparable playmates -- until, tragically, Su suddenly died from an infection resulting from a stick caught in his throat.

Ruth Harkness was shattered by Su's death, and her life began to spiral into depression. She tried another expedition to China and captured a third panda -- but before she could bring the new cub home, she was suddenly horror-struck by the implications of what she was doing: panda-hunting had become a fad and pandas were being taken out of their habitat in bunches to meet the demand from American zoos. She returned the bear to the forest and set it free -- and swore she'd never capture another animal again.

Ruth Harkness lived another eight years after that, working as a travel writer, but her zest for life was gone. She fell victim to alcoholism, and died alone in a hotel bathroom in 1947. Among the few scant posessions in her suitcase at the time of her death was a copy of "The Lady and the Panda," the book she'd written about her life with Su Lin, published just days before his death.

Ruth, Su Lin, and Mei Mei, February 1938.