DecoDame

One of the Regulars

- Messages

- 215

... It was sort of like the ending of "Animal Farm," if you get my drift....

Ah. Got it.

... It was sort of like the ending of "Animal Farm," if you get my drift....

John Lofgren Monkey Boots Shinki Horsebuttt - $1,136 The classic monkey boot silhouette in an incredibly rich Shinki russet horse leather.

John Lofgren Monkey Boots Shinki Horsebuttt - $1,136 The classic monkey boot silhouette in an incredibly rich Shinki russet horse leather.  Grant Stone Diesel Boot Dark Olive Chromexcel - $395 Goodyear welted, Horween Chromexcel, classic good looks.

Grant Stone Diesel Boot Dark Olive Chromexcel - $395 Goodyear welted, Horween Chromexcel, classic good looks.  Schott 568 Vandals Jacket - $1,250 The classic Perfecto motorcycle jacket, in a very special limited-edition Schott double rider style.

Schott 568 Vandals Jacket - $1,250 The classic Perfecto motorcycle jacket, in a very special limited-edition Schott double rider style.

I think this might be my favorite, I love when people can look around and realize that the thing they were making their money off is actually not a worthy path, might actually be harmful, and can step away from it. It takes a self-awareness and a self-respectability that seems to be all too rare.Been a while since I've done one of these, so here we go --

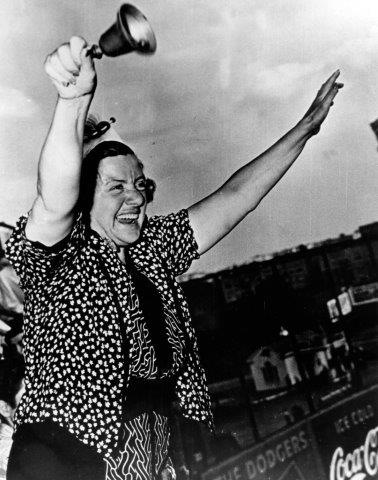

The world of American fashion design in the 1930s was a high-powered one, a world of elegance, style, and at its highest levels a world of demanding clientele. And it was a world in which an ambitious woman could accomplish much. But it was also a world that was artificial, cynical, and wasteful at its core -- with the constant demand for "the latest mode" making its products nearly as disposable as those of the present day. One woman who climbed high in this world, only to turn away from it in disgust, was Elizabeth Hawes.

<snip>

In 1938 she found an outlet for her growing disillusionment with the fashion industry, publishing a tell-all book, "Fashion Is Spinach." In this savagely witty volume, Hawes kicked over the fashion world and exposed its sleazy, manipulative underbelly. She also used the book to outline her own personal philosophy, in which she drew a sharp line between "Fashion," which she defined as an entirely artificial and commercial construct, and "Style," which was every woman's innate sense of what looked good on her, and encouraged her readers to adopt the latter and firmly reject the former.