Marc Chevalier

Gone Home

- Messages

- 18,192

- Location

- Los Feliz, Los Angeles, California

.

Short answer: the Ivy League silhouette ... and the Italians. Specifically, the House of Brioni.

Below is an excerpt from an article by G. Bruce Boyer about the Brioni "revolution." Longish, but well worth reading:

"... In 1945, Nazareno Fonticoli, an innovative master of the fine Italian tradition of custom tailoring, founded the Brioni atelier in Rome with Gaetano Savini, a natural talent for public relations. With a great respect for the classic contribution of Savile Row, but a sure feeling that the English had ignored the new attitudes towards men's clothes, Fonticoli and Savini set about to create their revolution.

It was a historic moment. By the late 1940s, most men had more leisure time, disposable income and access to consumer goods than their fathers had ever dreamed of.

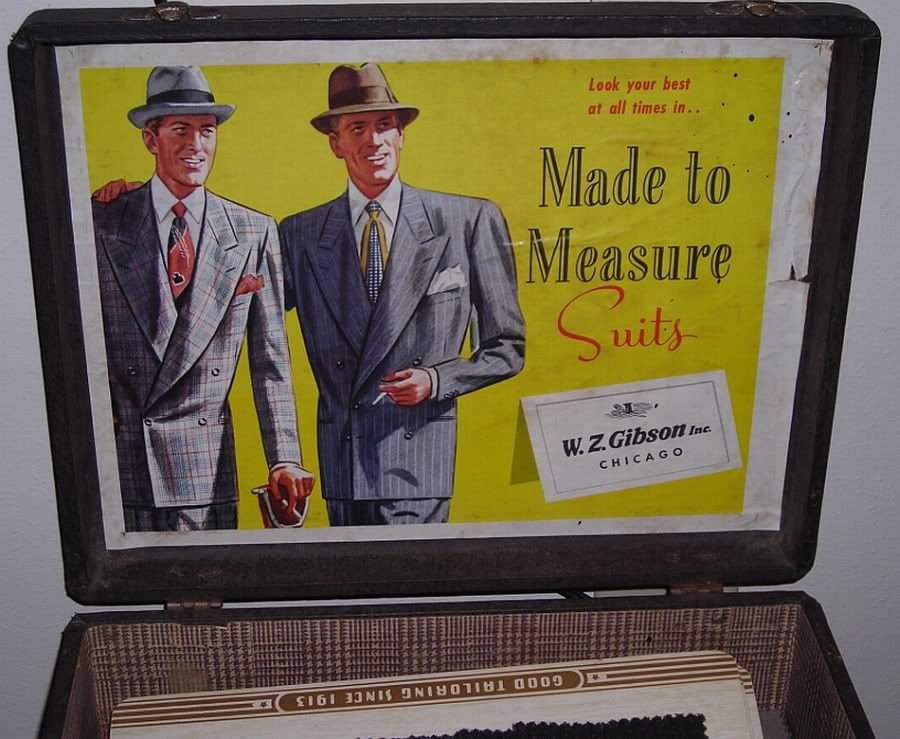

In clothing, the English-influenced "drape" look of the prewar period, with its oversized chest and shoulders, had become something of a caricature of itself. Jackets with enormous shoulder pads and inches of extra fabric in the chest and shoulder blade area began to sag and droop under their own weight. Trousers were being cut higher and higher, wider and wider, until they drowned the shoes and covered the torso halfway up the chest. It was a style particularly exaggerated in the United States as far as it could go by Hollywood heroes in the film noir genre and zoot-suited jazz hipsters. Clearly, the idea of drape styling could go no further.

Fonticoli and Savini began to attack most of the 1930s and 1940s ideas of what a suit should be, to systematically change its very line and expression. They cut away at the heavy silhouette that no longer conformed to the body, drastically reducing the bulk and padding. They seem, in retrospect, to have been among the first to realize that contemporary men, who lived in climate-controlled homes and offices, drove cars, and were slimmer and healthier, didn't want or need yards of heavily stiff and padded clothing.

The thinking was to reflect a thoroughly modern sensibility. Fonticoli and Savini began, in contemporary parlance, to "deconstruct" and completely redesign the garment, to emphasize lightness and trimness. But this was not merely a revolution of line and form. There was a decided movement away from the drab and somber uniformity of traditional business gray worsted toward a whole new liberating palate of brilliant colors and untraditional fabrics.

The silhouette they devised eventually came to be thought of in the United States (although not by them) as the Continental Look, and it swept away both the hyperdrapey style that was so prevalent before the war and the sack-cut look of the Ivy League style that was gaining prominence after the war. The result was a pared-down approach to tailoring, with a dash of flamboyant color and texture for good measure. It was indeed a revolution.

Technically, the Brioni jacket of the 1950s sat closer to the body, shoulders were narrowed and the chest tightened and smoothed. The waist was subtly shaped. The skirt (the part of the jacket from the waist down) sat closer to the hips and was imperceptibly cut away in front in two graceful arcs. Backs were either ventless or had short side vents, sleeves were narrowed, pocket flaps were often eliminated in favor of simple besoms, and a two-button stance was raised slightly to provide a longer line.

Trouser legs were trimmed, pleats and cuffs abandoned, and quarter-top pockets were often substituted for on-seam ones. In effect, Brioni experimented with the whole silhouette and all the details until everything worked together to produce a new harmony of slimness and spareness of silhouette, played off against more vibrant colors and a sense of texture.

It was a reaction to the top-heavy, supermuscular look of the past. There was nothing retro or nostalgic about it. The Brioni approach was clothing for a new age. It made a man look slimmer and younger and more vibrant. How could it miss? The shop on the Via Barberini grew from 10 tailors to 50 in its first decade in business. The Brioni look came to define modernism in menswear.

The vibrancy came from the new look in fabric and color advocated by Brioni. Apart from a few tropical worsteds and summer cottons, most men were still wearing the traditional twills, tweeds and flannels that their fathers and grandfathers had worn, and they were wearing them in the same Victorian suiting shades of dark gray, navy and brown--and in the same weights: even summer suits would weigh in at several pounds. A seersucker sports jacket, blue blazer or tan linen suit were the only exceptions to that somber Anglo-Saxon wardrobe.

"But why shouldn't men be more colorful?" Savini asked. "Why can't a man be elegant without being either dull or foppish? That's what we're interested in." Why, for example, couldn't a man wear a suit of silk shantung, and why couldn't it be in a flattering pastel shade, or rich tobacco brown? Or perhaps a cream-and-chocolate minicheck-houndstooth business suit in a super-lightweight tropical worsted? Why not? ..."

.

Short answer: the Ivy League silhouette ... and the Italians. Specifically, the House of Brioni.

Below is an excerpt from an article by G. Bruce Boyer about the Brioni "revolution." Longish, but well worth reading:

"... In 1945, Nazareno Fonticoli, an innovative master of the fine Italian tradition of custom tailoring, founded the Brioni atelier in Rome with Gaetano Savini, a natural talent for public relations. With a great respect for the classic contribution of Savile Row, but a sure feeling that the English had ignored the new attitudes towards men's clothes, Fonticoli and Savini set about to create their revolution.

It was a historic moment. By the late 1940s, most men had more leisure time, disposable income and access to consumer goods than their fathers had ever dreamed of.

In clothing, the English-influenced "drape" look of the prewar period, with its oversized chest and shoulders, had become something of a caricature of itself. Jackets with enormous shoulder pads and inches of extra fabric in the chest and shoulder blade area began to sag and droop under their own weight. Trousers were being cut higher and higher, wider and wider, until they drowned the shoes and covered the torso halfway up the chest. It was a style particularly exaggerated in the United States as far as it could go by Hollywood heroes in the film noir genre and zoot-suited jazz hipsters. Clearly, the idea of drape styling could go no further.

Fonticoli and Savini began to attack most of the 1930s and 1940s ideas of what a suit should be, to systematically change its very line and expression. They cut away at the heavy silhouette that no longer conformed to the body, drastically reducing the bulk and padding. They seem, in retrospect, to have been among the first to realize that contemporary men, who lived in climate-controlled homes and offices, drove cars, and were slimmer and healthier, didn't want or need yards of heavily stiff and padded clothing.

The thinking was to reflect a thoroughly modern sensibility. Fonticoli and Savini began, in contemporary parlance, to "deconstruct" and completely redesign the garment, to emphasize lightness and trimness. But this was not merely a revolution of line and form. There was a decided movement away from the drab and somber uniformity of traditional business gray worsted toward a whole new liberating palate of brilliant colors and untraditional fabrics.

The silhouette they devised eventually came to be thought of in the United States (although not by them) as the Continental Look, and it swept away both the hyperdrapey style that was so prevalent before the war and the sack-cut look of the Ivy League style that was gaining prominence after the war. The result was a pared-down approach to tailoring, with a dash of flamboyant color and texture for good measure. It was indeed a revolution.

Technically, the Brioni jacket of the 1950s sat closer to the body, shoulders were narrowed and the chest tightened and smoothed. The waist was subtly shaped. The skirt (the part of the jacket from the waist down) sat closer to the hips and was imperceptibly cut away in front in two graceful arcs. Backs were either ventless or had short side vents, sleeves were narrowed, pocket flaps were often eliminated in favor of simple besoms, and a two-button stance was raised slightly to provide a longer line.

Trouser legs were trimmed, pleats and cuffs abandoned, and quarter-top pockets were often substituted for on-seam ones. In effect, Brioni experimented with the whole silhouette and all the details until everything worked together to produce a new harmony of slimness and spareness of silhouette, played off against more vibrant colors and a sense of texture.

It was a reaction to the top-heavy, supermuscular look of the past. There was nothing retro or nostalgic about it. The Brioni approach was clothing for a new age. It made a man look slimmer and younger and more vibrant. How could it miss? The shop on the Via Barberini grew from 10 tailors to 50 in its first decade in business. The Brioni look came to define modernism in menswear.

The vibrancy came from the new look in fabric and color advocated by Brioni. Apart from a few tropical worsteds and summer cottons, most men were still wearing the traditional twills, tweeds and flannels that their fathers and grandfathers had worn, and they were wearing them in the same Victorian suiting shades of dark gray, navy and brown--and in the same weights: even summer suits would weigh in at several pounds. A seersucker sports jacket, blue blazer or tan linen suit were the only exceptions to that somber Anglo-Saxon wardrobe.

"But why shouldn't men be more colorful?" Savini asked. "Why can't a man be elegant without being either dull or foppish? That's what we're interested in." Why, for example, couldn't a man wear a suit of silk shantung, and why couldn't it be in a flattering pastel shade, or rich tobacco brown? Or perhaps a cream-and-chocolate minicheck-houndstooth business suit in a super-lightweight tropical worsted? Why not? ..."

.