Francis James Barraud was born in Liverpool, England on June 16, 1856 and came from a family of painters. His father, Henry (1811-1874), had been a noted painter. And his Uncle William, Henry’s older brother, had also been a noted painter. Most of their works covered wildlife, fox hunting and the horses known as bay hunters. In fact, William and Henry collaborated on a number of paintings which were featured on various sporting magazine covers which, for better or worse, helped popularize fox hunting, before William’s untimely death in 1850.

Francis followed in his father’s footsteps as did his older brother, Mark. Francis studied first at the Royal Academy Schools, then at Heatherley’s Art School in London and finally at Beaux Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. Francis became a scenic artist while Mark eked out a living painting stage sets. Francis originally set about painting scenes of fox hunting producing his own “Bay Hunter” but soon branched out into other areas. Francis, however, could not achieve his father’s fame. Even today, many Henry Barraud portraits can be found on the internet (as can William’s) but those of his son, with one notable exception, which we will be investigating at length, are very hard to come by. Times were changing and Henry was worried that his sons would not be able to find rich patrons to fund their art. But Francis was not deterred and continued trying to forge his own style and identity as an artist and found a degree of popularity with his oil paintings and watercolors.

Like many serious painters, Francis Barraud made money on the side as an illustrator. And like many serious painters, he found such work somewhat demeaning but it paid bills. His handiwork as an illustrator for an 1882 edition of Routledge’s Every Girl’s Annual where he did both cover and inside pictures are quite lovely and competent.

Mark Barraud, however, lived on the edge of poverty, never achieving as much fame as his father or even the nominal fame of his brother. Life was not easy for him as a result and he was given to hard living, particularly drink, which took a toll on his health.

Sometime in 1883 or 4, a mixed bull/fox terrier (although it may have been part Jack Russell terrier) was born somewhere around Bristol, England. He was a plucky little stray puppy when Mark Barraud encountered him in 1884 while out on a jaunt. He took the dog home to his wife and they found him a faithful companion with the tendency to nip at backs of visitors’ legs so they named the dog Nipper. For three years, Barraud and Nipper were man and man’s best friend. Poverty and ill health, however, caught up with Barraud and he died in Bristol in 1887 at age 39. Nipper was taken to Liverpool, Lancashire where Francis lived.

Francis Barraud quickly became fond of Nipper whom he found amiable, curious and intelligent. He would take Nipper to the Richmond Park and the dog would frolic and chase other animals, once killing a pheasant that Barraud had not the chutzpah to tuck under his arm.

While Barraud was in his studio working on a painting, he would play his phonograph, a cylinder machine. He got the idea from his noted contemporary Sir Hubert von Herkomer (1849-1914) who kept such a machine in his studio to set his subjects at ease while they posed. Nipper’s natural curiosity got the best of him and he would sit close to the horn speaker, ears pricked up, ticking his head from side to side as he listened to the mysterious sounds and voices issue forth from the bell. To Barraud, it seemed as though the dog might have thought the voice coming from the horn was that of Mark Barraud. “I had often noticed how puzzled he was to make out where the voice came from,” Francis later stated. The image stayed with him.

In 1895, Nipper went to Kingston-upon-Thames in Surrey to keep company to Mark Barraud’s widow but, alas, he died in September of that year at the age of 11 or 12. He was buried in Kingston-upon-Thames.

Three years later, Francis Barraud was back in his studio listening to his phonograph when he thought of Nipper staring intently into the bell of the speaker horn. He remembered how he fancied that Nipper might have thought he was hearing his dead former owner. He began to work on a new painting depicting that scene. He painted Nipper seated before a cylinder-player staring into the bell.

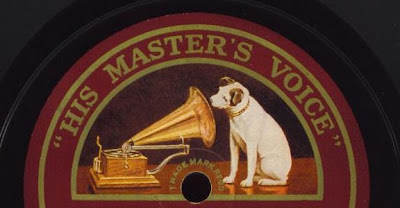

Barraud titled the work “Dog Looking at and Listening to a Phonograph” and registered the painting under that title in February of 1898. Going with his original impression of the dog hearing his dead master’s voice, Barraud retitled the painting “His Master’s Voice.” If this was in hopes that the Royal Academy would exhibit the work, Barraud was sadly mistaken. They turned him away. Barraud hoped to get “His Master’s Voice” published in a few magazines but they said the painting did not make sense. Barraud went to the Edison Bell Company who made the phonograph seen in the painting. They were not interested in purchasing it because, they told him, dogs don’t listen to phonographs (weird reasoning when Nipper did indeed listen to it and they could have easily told customers as a sales gimmick that if the machine can fool a dog’s sharp ears imagine how real it must sound).

A friend of Barraud’s told him the horn was too dark to be properly seen and a nice golden brass one might spice up the picture. Barraud saw the logic and thought the whole painting should be lighter. He called on the newly-formed Gramophone Company at Maiden Lane and spoke to the company president, William Barry Owen, requesting a golden horn attachment for loan. Barraud showed Owen the painting and what changes he wanted to make. Owen, in turn, needed a trademark for his company knowing how important a good distinctive trademark is to the success of a business. Barraud recalled years later that Owen asked him if the painting was for sale and if he would mind changing the phonograph to a gramophone. This was, of course, precisely what Barraud was hoping for and replied that the painting was indeed for sale and immediately set to work the revising the picture as requested having secured a gramophone from the company to employ as a model. When he finished the painting, Barraud dropped it off at Maiden Lane and waited nervously for a response.

He got one when a letter arrived from the Gramophone Company offices on the 15th of September 1899 offering Barraud £50 for reproduction rights and another £50 for the artist’s copyright. In short, they offered him £100 for the work. Not at all a bad sum in those days (in fact, not at all a bad sum these days, just ask any struggling artist) and Barraud happily and gratefully accepted. The Gramophone Company was now the legal owner of the painting and the image on it and Barraud no doubt did a bit of celebrating with his £100. Did he ever dare to guess how famous that painting would become?

By the way, a few sources say that Nipper and gramophone are poised atop a coffin and that is why he thinks he hears his master’s voice coming from the horn. Other sources say that this is not true—both subjects are depicted seated on a tabletop in Barraud’s studio. I’ll leave that to the reader to decide which story sounds better.

Francis followed in his father’s footsteps as did his older brother, Mark. Francis studied first at the Royal Academy Schools, then at Heatherley’s Art School in London and finally at Beaux Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. Francis became a scenic artist while Mark eked out a living painting stage sets. Francis originally set about painting scenes of fox hunting producing his own “Bay Hunter” but soon branched out into other areas. Francis, however, could not achieve his father’s fame. Even today, many Henry Barraud portraits can be found on the internet (as can William’s) but those of his son, with one notable exception, which we will be investigating at length, are very hard to come by. Times were changing and Henry was worried that his sons would not be able to find rich patrons to fund their art. But Francis was not deterred and continued trying to forge his own style and identity as an artist and found a degree of popularity with his oil paintings and watercolors.

Like many serious painters, Francis Barraud made money on the side as an illustrator. And like many serious painters, he found such work somewhat demeaning but it paid bills. His handiwork as an illustrator for an 1882 edition of Routledge’s Every Girl’s Annual where he did both cover and inside pictures are quite lovely and competent.

Mark Barraud, however, lived on the edge of poverty, never achieving as much fame as his father or even the nominal fame of his brother. Life was not easy for him as a result and he was given to hard living, particularly drink, which took a toll on his health.

Sometime in 1883 or 4, a mixed bull/fox terrier (although it may have been part Jack Russell terrier) was born somewhere around Bristol, England. He was a plucky little stray puppy when Mark Barraud encountered him in 1884 while out on a jaunt. He took the dog home to his wife and they found him a faithful companion with the tendency to nip at backs of visitors’ legs so they named the dog Nipper. For three years, Barraud and Nipper were man and man’s best friend. Poverty and ill health, however, caught up with Barraud and he died in Bristol in 1887 at age 39. Nipper was taken to Liverpool, Lancashire where Francis lived.

Francis Barraud quickly became fond of Nipper whom he found amiable, curious and intelligent. He would take Nipper to the Richmond Park and the dog would frolic and chase other animals, once killing a pheasant that Barraud had not the chutzpah to tuck under his arm.

While Barraud was in his studio working on a painting, he would play his phonograph, a cylinder machine. He got the idea from his noted contemporary Sir Hubert von Herkomer (1849-1914) who kept such a machine in his studio to set his subjects at ease while they posed. Nipper’s natural curiosity got the best of him and he would sit close to the horn speaker, ears pricked up, ticking his head from side to side as he listened to the mysterious sounds and voices issue forth from the bell. To Barraud, it seemed as though the dog might have thought the voice coming from the horn was that of Mark Barraud. “I had often noticed how puzzled he was to make out where the voice came from,” Francis later stated. The image stayed with him.

In 1895, Nipper went to Kingston-upon-Thames in Surrey to keep company to Mark Barraud’s widow but, alas, he died in September of that year at the age of 11 or 12. He was buried in Kingston-upon-Thames.

Three years later, Francis Barraud was back in his studio listening to his phonograph when he thought of Nipper staring intently into the bell of the speaker horn. He remembered how he fancied that Nipper might have thought he was hearing his dead former owner. He began to work on a new painting depicting that scene. He painted Nipper seated before a cylinder-player staring into the bell.

Barraud titled the work “Dog Looking at and Listening to a Phonograph” and registered the painting under that title in February of 1898. Going with his original impression of the dog hearing his dead master’s voice, Barraud retitled the painting “His Master’s Voice.” If this was in hopes that the Royal Academy would exhibit the work, Barraud was sadly mistaken. They turned him away. Barraud hoped to get “His Master’s Voice” published in a few magazines but they said the painting did not make sense. Barraud went to the Edison Bell Company who made the phonograph seen in the painting. They were not interested in purchasing it because, they told him, dogs don’t listen to phonographs (weird reasoning when Nipper did indeed listen to it and they could have easily told customers as a sales gimmick that if the machine can fool a dog’s sharp ears imagine how real it must sound).

A friend of Barraud’s told him the horn was too dark to be properly seen and a nice golden brass one might spice up the picture. Barraud saw the logic and thought the whole painting should be lighter. He called on the newly-formed Gramophone Company at Maiden Lane and spoke to the company president, William Barry Owen, requesting a golden horn attachment for loan. Barraud showed Owen the painting and what changes he wanted to make. Owen, in turn, needed a trademark for his company knowing how important a good distinctive trademark is to the success of a business. Barraud recalled years later that Owen asked him if the painting was for sale and if he would mind changing the phonograph to a gramophone. This was, of course, precisely what Barraud was hoping for and replied that the painting was indeed for sale and immediately set to work the revising the picture as requested having secured a gramophone from the company to employ as a model. When he finished the painting, Barraud dropped it off at Maiden Lane and waited nervously for a response.

He got one when a letter arrived from the Gramophone Company offices on the 15th of September 1899 offering Barraud £50 for reproduction rights and another £50 for the artist’s copyright. In short, they offered him £100 for the work. Not at all a bad sum in those days (in fact, not at all a bad sum these days, just ask any struggling artist) and Barraud happily and gratefully accepted. The Gramophone Company was now the legal owner of the painting and the image on it and Barraud no doubt did a bit of celebrating with his £100. Did he ever dare to guess how famous that painting would become?

By the way, a few sources say that Nipper and gramophone are poised atop a coffin and that is why he thinks he hears his master’s voice coming from the horn. Other sources say that this is not true—both subjects are depicted seated on a tabletop in Barraud’s studio. I’ll leave that to the reader to decide which story sounds better.