- Article Format

- Article View

By Scott Daniels

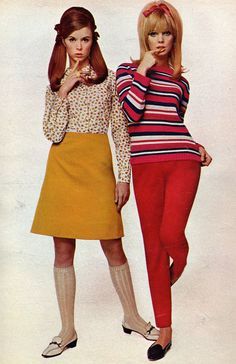

The 20th century saw dramatic changes in fashion for women.

Rereading that sentence, “dramatic” feels like too silly a word to use; comparing a dress from 1900 to one of the 1960s feels much more like witnessing the arrival of an entirely new species.

Along the way, fashion houses, chiefly and famously found in Paris, helped further this major evolution, paired tightly with the personalities at their heads. Many designs were ground breaking and immediately identifiable as coming from this or that salon. In turn, innovation were carried into the world’s leading retail establishments, finally distilling down into copies and derivations available via catalogs and the local dressmaker, where a lady could visit to see the most recent arrivals and spend time with a fitter prepared to make appropriate alterations to off-the-rack purchases.

But the ideas, the major leaps forward, came from the fashion designers with the drive, talent and personal charisma to match their extraordinary creations.

Cristobal Balenciaga

Still revered as the king of couturiers, Cristobal Balenciaga (1885-1972, active 1937-1968) was also teacher to many of the most famous designers who followed him. Born in Spain, Balenciaga spoke of the need for a couturier to be “an architect for design, a sculptor for shape, a painter for color, a musician for harmony and a philosopher for temperance.” He was all these, creating dresses which his clients reported offering unheard of freedom of movement inside the layers of cloth. Balenciaga was foremost a master tailor, able to create custom creations correcting stooped shoulders, rounded stomach and wider hips, making such realities disappear as if by some miracle. His clothes felt sculpted, and indeed his work was ex-rayed much later to reveal interior weights, bone supports and remarkable detail, all hidden in glamorous, perfectly fitted glory.

Balenciaga used a variety of models hand picked to show off his own creations, some of them rail thin, others more fully figured, most in their thirties or older; some were described as “monsters” by the fashion press. Balenciaga kept his monsters on staff for years, requiring retailers and photographers to use Balenciaga house models for all fashion shoots.

Dovima by Richard Avedon

Unlike the the rather wild and noisy fashion showings of today, or even by mid 20th century standards, a Balenciaga show, conducted daily at his salon in Paris, was an exclusive, hushed affair. One entered through a display of handbags, gloves and perfumes and rose to the third floor salon (assuming entry was granted by a gatekeeper checking credentials) via a tiny, red leather upholstered lift. Attendees spoke in whispers normally reserved for church sanctuaries, and no design names or numbers were called out for the two-hour event. Models carried discreet cards with numbers. The slightest criticism or misbehavior could ban client, store buyer or press for several seasons.

He avoided publicity, even staying away from major fittings in his design house chambers, giving just one interview in his lifetime.

Balenciaga’s pupils in the fashion design classes which he taught included Oscar de la Renta, André Courrèges, Emanuel Ungaro, Mila Schön, and Hubert de Givenchy.

Gabrielle, “Coco” Chanel

Coco Chanel at her Paris Ritz Hotel Apartment

As much an outsized personality as fashion trend setter, Coco Chanel (1883-1971, active 1913-1971) was born into grievous poverty to unwed parents and raised by nuns.

She could not sketch, disliked sewing. She was poorly educated. She was as far removed from French society as is possible to imagine.

Yet, she built a fashion house credited with several style innovations and her designs were as widely copied and admired as her imminently quotable pronouncements. Her life was a splendidly Dickensian rags-to-riches tale, filled with the experiences she used with nuance and insight to infuse her creations. Her designs were accepted enthusiastically by women eager for escape from corsets and constraints. Her controversial personal life kept her on the verge of public shunning, especially in midlife.

In her early 20s, she lived on the estate of a well-connected lover, who polished and refined the roughness of her origins, teaching her to ride horses and carry herself with dignity. She was able, throughout her adult life, to move confidently through, and often occupy the epicenter of, fashionable Paris society as she brought them simple, elegant designs frequently borrowing from the clothing of the poor: Maid uniform cuffs. Street seller scarves. Cotton jersey fabrics. Nun habits—bits of each found their way into the House of Chanel.

During WWII, unsavory collaboration with the occupying Nazis and a reprehensible antisemitism clouded the remainder of her career.

Unlike the all but invisible Balenciaga, Chanel sought the spotlight. She is widely remembered for her pithy life wisdoms.

A blue fringed Chanel dress, 1927, on Display at the Cleveland Museum of Art, 2017.

“Dress shabbily and they remember the dress; dress impeccably and they remember the woman.”

“A girl should be two things: classy and fabulous.”

“The best things in life are free; the second best are very expensive.”

She is primarily remembered for the Chanel suit, with straight lines and a hemline just below the knee, the little black dress, and her signature scent, Chanel No5.

Cristian Dior

Christian Dior with model sporting The New Look.

One of the best-known names among the public in current fashion, many might be surprised to know that Christian Dior (1905-1957, active 1946-1957) died more than sixty years ago, at the peak of success. His fashion house at the time of his death was earning upwards of $200 million.

Dior, unlike Chanel, began life in relative security, one of five children born to a well-off businessman in France. Leaving school as a young man, his father sufficiently overcame his disappointment to set Christian up with a Paris art gallery. The gallery, though successful, went bust along with the patriarchal Dior in 1929, after which the young designer made do by selling his fashion sketches until securing a place with couturier Lucien Long.

It was in 1947 that Dior’s greatest contribution burst onto the Paris fashion stage: The New Look.

The New Look: accentuating the feminine.

During the second world war, women’s fashion became quite square-shouldered, almost military uniform like (think Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce). The times called for strong women filling traditionally male roles, and their clothing reflected the tough lady image.

The New Look instantly changed all that, with tight bodices and wide, flowing, feminine silhouettes softening the female figure considerably, as men returned home from the war and expected their wives to return to their feminine roles. We remember Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, Jackie Kennedy, Rita Hayworth, Margot Fonteyn, and many other well-known Dior clients appearing in Dior New Look creations.

Dior was the first couturier to license his name and designs for wider production. The practice soon became an industry standard.

Many of the designer’s influences are still felt today, and the Dior brand is still flourishing. Christian Dior died after a third heart attack at age 52, after giving the nod to Yves St Laurent as successor at Dior.

The 20th century saw dramatic changes in fashion for women.

Rereading that sentence, “dramatic” feels like too silly a word to use; comparing a dress from 1900 to one of the 1960s feels much more like witnessing the arrival of an entirely new species.

Along the way, fashion houses, chiefly and famously found in Paris, helped further this major evolution, paired tightly with the personalities at their heads. Many designs were ground breaking and immediately identifiable as coming from this or that salon. In turn, innovation were carried into the world’s leading retail establishments, finally distilling down into copies and derivations available via catalogs and the local dressmaker, where a lady could visit to see the most recent arrivals and spend time with a fitter prepared to make appropriate alterations to off-the-rack purchases.

But the ideas, the major leaps forward, came from the fashion designers with the drive, talent and personal charisma to match their extraordinary creations.

Cristobal Balenciaga

Still revered as the king of couturiers, Cristobal Balenciaga (1885-1972, active 1937-1968) was also teacher to many of the most famous designers who followed him. Born in Spain, Balenciaga spoke of the need for a couturier to be “an architect for design, a sculptor for shape, a painter for color, a musician for harmony and a philosopher for temperance.” He was all these, creating dresses which his clients reported offering unheard of freedom of movement inside the layers of cloth. Balenciaga was foremost a master tailor, able to create custom creations correcting stooped shoulders, rounded stomach and wider hips, making such realities disappear as if by some miracle. His clothes felt sculpted, and indeed his work was ex-rayed much later to reveal interior weights, bone supports and remarkable detail, all hidden in glamorous, perfectly fitted glory.

Balenciaga used a variety of models hand picked to show off his own creations, some of them rail thin, others more fully figured, most in their thirties or older; some were described as “monsters” by the fashion press. Balenciaga kept his monsters on staff for years, requiring retailers and photographers to use Balenciaga house models for all fashion shoots.

Dovima by Richard Avedon

Unlike the the rather wild and noisy fashion showings of today, or even by mid 20th century standards, a Balenciaga show, conducted daily at his salon in Paris, was an exclusive, hushed affair. One entered through a display of handbags, gloves and perfumes and rose to the third floor salon (assuming entry was granted by a gatekeeper checking credentials) via a tiny, red leather upholstered lift. Attendees spoke in whispers normally reserved for church sanctuaries, and no design names or numbers were called out for the two-hour event. Models carried discreet cards with numbers. The slightest criticism or misbehavior could ban client, store buyer or press for several seasons.

He avoided publicity, even staying away from major fittings in his design house chambers, giving just one interview in his lifetime.

Balenciaga’s pupils in the fashion design classes which he taught included Oscar de la Renta, André Courrèges, Emanuel Ungaro, Mila Schön, and Hubert de Givenchy.

Gabrielle, “Coco” Chanel

Coco Chanel at her Paris Ritz Hotel Apartment

As much an outsized personality as fashion trend setter, Coco Chanel (1883-1971, active 1913-1971) was born into grievous poverty to unwed parents and raised by nuns.

She could not sketch, disliked sewing. She was poorly educated. She was as far removed from French society as is possible to imagine.

Yet, she built a fashion house credited with several style innovations and her designs were as widely copied and admired as her imminently quotable pronouncements. Her life was a splendidly Dickensian rags-to-riches tale, filled with the experiences she used with nuance and insight to infuse her creations. Her designs were accepted enthusiastically by women eager for escape from corsets and constraints. Her controversial personal life kept her on the verge of public shunning, especially in midlife.

In her early 20s, she lived on the estate of a well-connected lover, who polished and refined the roughness of her origins, teaching her to ride horses and carry herself with dignity. She was able, throughout her adult life, to move confidently through, and often occupy the epicenter of, fashionable Paris society as she brought them simple, elegant designs frequently borrowing from the clothing of the poor: Maid uniform cuffs. Street seller scarves. Cotton jersey fabrics. Nun habits—bits of each found their way into the House of Chanel.

During WWII, unsavory collaboration with the occupying Nazis and a reprehensible antisemitism clouded the remainder of her career.

Unlike the all but invisible Balenciaga, Chanel sought the spotlight. She is widely remembered for her pithy life wisdoms.

A blue fringed Chanel dress, 1927, on Display at the Cleveland Museum of Art, 2017.

“Dress shabbily and they remember the dress; dress impeccably and they remember the woman.”

“A girl should be two things: classy and fabulous.”

“The best things in life are free; the second best are very expensive.”

She is primarily remembered for the Chanel suit, with straight lines and a hemline just below the knee, the little black dress, and her signature scent, Chanel No5.

Cristian Dior

Christian Dior with model sporting The New Look.

One of the best-known names among the public in current fashion, many might be surprised to know that Christian Dior (1905-1957, active 1946-1957) died more than sixty years ago, at the peak of success. His fashion house at the time of his death was earning upwards of $200 million.

Dior, unlike Chanel, began life in relative security, one of five children born to a well-off businessman in France. Leaving school as a young man, his father sufficiently overcame his disappointment to set Christian up with a Paris art gallery. The gallery, though successful, went bust along with the patriarchal Dior in 1929, after which the young designer made do by selling his fashion sketches until securing a place with couturier Lucien Long.

It was in 1947 that Dior’s greatest contribution burst onto the Paris fashion stage: The New Look.

The New Look: accentuating the feminine.

During the second world war, women’s fashion became quite square-shouldered, almost military uniform like (think Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce). The times called for strong women filling traditionally male roles, and their clothing reflected the tough lady image.

The New Look instantly changed all that, with tight bodices and wide, flowing, feminine silhouettes softening the female figure considerably, as men returned home from the war and expected their wives to return to their feminine roles. We remember Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, Jackie Kennedy, Rita Hayworth, Margot Fonteyn, and many other well-known Dior clients appearing in Dior New Look creations.

Dior was the first couturier to license his name and designs for wider production. The practice soon became an industry standard.

Many of the designer’s influences are still felt today, and the Dior brand is still flourishing. Christian Dior died after a third heart attack at age 52, after giving the nod to Yves St Laurent as successor at Dior.