- Article Format

- Article View

By Scott Daniels

It’s a decent bet that much of what you assume to be true about the hard-boiled noir crime dramas of The Era originates in the popular media of the time. Men and women spoke this way. They wore these things. They cracked wise with these phrases. They drank those cocktails. We get a lot of it from the movies, but films made under the Motion Picture Production Code were heavily censored and sanitized versions, watered down to meet the whitewashed sensibilities of the Hays Office.

As they say, the book is better, and if you want to immerse yourself in the popularized version of life in speakeasies, back alley brawls, casual sex, purple-tinted, swear laced air, and the occasional dip into drugs, you have to read the novels.

Depression-era crime stories are some of the best, grittiest reads to be found in any genre. Bonus: They’re generally short, and tend to be easily found in compendiums of an author’s work. You should be able to find any of these in later editions at any used bookstore for under $5.

The Thin Man

Dashiell Hammett

Knopf, 1934

First published in Redbook in 1933, The Thin Man appeared soon after in novel form. It was Hammett’s last published novel, though he lived on until 1961. Hammett is widely regarded as the finest author in the mystery genre, with quick-moving plots, well-crafted dialogue and tight stories.

The Thin Man introduces Nick and Nora Charles. Nick is a former detective who has sworn off sleuthing in favor of managing his lovely, witty wife’s fortune while drinking away the hours in speaks and hotel rooms. He finds himself reluctantly drawn into solving a murder mystery when the titular character turns up missing, then dead.

Later turned into a series of films starring William Powell and Myrna Loy, the dialogue between the two is even better in the book.

Nick: “I want a drink, please.”

Nora: “Why don’t you have some breakfast first?”

Nick: “It’s too early for breakfast.”

The Maltese Falcon

Dashiell Hammett

Knopf, 1930

Another well-known detective comes to life in this Hammett Novel: Samuel Spade. While Nick Charles is urbane, charming, and smooth, Sam Spade is tough, suspicious and street wise. That Hammett is able to so fully create very different characters in the same line of work speaks to his own experience as a real life detective and masterful skill as writer.

Spade’s partner, Miles Archer, is shot dead after the arrival of a damsel seeking their detective agency’s help. Spade is left to untangle a knotted web of intrigue, greed and smokescreens while capturing Archer’s murderer. The book is populated with memorable characters and surpasses the Bogart film in realism, though you’ll probably read it with the actors from the movie in mind.

The Postman Always Rings Twice

James M. Cain

Knopf, 1934

A drifter (Frank Chambers) looking for the easy score blows into a diner owned by a foolish Greek (Nick Papadakis) and his stunning, neglected wife Cora. Gaining the trust and admiration of the husband, Chambers takes a job at the diner, and is quickly having rough and tumble sex with Mrs. Papadakis while the Greek is away. Sharing both physical chemistry and a desire to find some stake money to start over someplace else, the elicit couple hatch a sinister plot with plenty of opportunities for derailment and trouble.

Double Indemnity

James M. Cain

Knopf, 1941

Published well past past Prohibition, on the tails of the Great Depression, and just before American entry into World War Two, Double Indemnity has an altogether different feel from Cain’s earlier work.

Walter Huff (Neff in the later film version) is a top selling insurance salesman who does things carefully and by the book. Then he meets Phyllis Nirdlinger, wife of a client who wants to get rid of her husband and cash in on the fat life insurance policy. Huff falls hard and is drawn into the plot against his own better judgment and instinctual decency.

Cain loosely based the story on the real life wife-boyfriend-dead husband-insurance fraud case of Ruth Snyder, which he covered as a journalist in 1927.

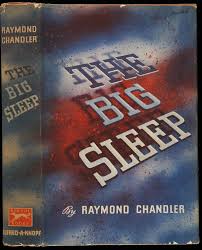

The Big Sleep

Raymond Chandler

Knopf, 1939

The Big Sleep works as a crime novel even though the thing is a complicated mess, with loose ends, red herrings, and unresolved plot elements. Chandler himself was unable to sort it all out and explain major parts of it after its successful publication. Chandler often cobbled previously published short stories into a single novel, and The Big Sleep reworks two dissimilar tales, “Killer in the Rain" (1935) and "The Curtain" (1936).

When the book was turned into a film, director Howard Hawks asked the key question, “Who killed the chauffeur?”

Chandler replied “I have no idea.”

The Big Sleep introduces the iconic detective Phillip Marlowe, who is hired to track down the blackmailer of wealthy old man General Sternwood’s wild daughter, Carmen. Marlowe follows a trail of drugs, pornography, corpses and booksellers in an ever expanding plot line which, despite its many twists, is engrossing for the reader.

It’s a decent bet that much of what you assume to be true about the hard-boiled noir crime dramas of The Era originates in the popular media of the time. Men and women spoke this way. They wore these things. They cracked wise with these phrases. They drank those cocktails. We get a lot of it from the movies, but films made under the Motion Picture Production Code were heavily censored and sanitized versions, watered down to meet the whitewashed sensibilities of the Hays Office.

As they say, the book is better, and if you want to immerse yourself in the popularized version of life in speakeasies, back alley brawls, casual sex, purple-tinted, swear laced air, and the occasional dip into drugs, you have to read the novels.

Depression-era crime stories are some of the best, grittiest reads to be found in any genre. Bonus: They’re generally short, and tend to be easily found in compendiums of an author’s work. You should be able to find any of these in later editions at any used bookstore for under $5.

The Thin Man

Dashiell Hammett

Knopf, 1934

First published in Redbook in 1933, The Thin Man appeared soon after in novel form. It was Hammett’s last published novel, though he lived on until 1961. Hammett is widely regarded as the finest author in the mystery genre, with quick-moving plots, well-crafted dialogue and tight stories.

The Thin Man introduces Nick and Nora Charles. Nick is a former detective who has sworn off sleuthing in favor of managing his lovely, witty wife’s fortune while drinking away the hours in speaks and hotel rooms. He finds himself reluctantly drawn into solving a murder mystery when the titular character turns up missing, then dead.

Later turned into a series of films starring William Powell and Myrna Loy, the dialogue between the two is even better in the book.

Nick: “I want a drink, please.”

Nora: “Why don’t you have some breakfast first?”

Nick: “It’s too early for breakfast.”

The Maltese Falcon

Dashiell Hammett

Knopf, 1930

Another well-known detective comes to life in this Hammett Novel: Samuel Spade. While Nick Charles is urbane, charming, and smooth, Sam Spade is tough, suspicious and street wise. That Hammett is able to so fully create very different characters in the same line of work speaks to his own experience as a real life detective and masterful skill as writer.

Spade’s partner, Miles Archer, is shot dead after the arrival of a damsel seeking their detective agency’s help. Spade is left to untangle a knotted web of intrigue, greed and smokescreens while capturing Archer’s murderer. The book is populated with memorable characters and surpasses the Bogart film in realism, though you’ll probably read it with the actors from the movie in mind.

The Postman Always Rings Twice

James M. Cain

Knopf, 1934

A drifter (Frank Chambers) looking for the easy score blows into a diner owned by a foolish Greek (Nick Papadakis) and his stunning, neglected wife Cora. Gaining the trust and admiration of the husband, Chambers takes a job at the diner, and is quickly having rough and tumble sex with Mrs. Papadakis while the Greek is away. Sharing both physical chemistry and a desire to find some stake money to start over someplace else, the elicit couple hatch a sinister plot with plenty of opportunities for derailment and trouble.

Double Indemnity

James M. Cain

Knopf, 1941

Published well past past Prohibition, on the tails of the Great Depression, and just before American entry into World War Two, Double Indemnity has an altogether different feel from Cain’s earlier work.

Walter Huff (Neff in the later film version) is a top selling insurance salesman who does things carefully and by the book. Then he meets Phyllis Nirdlinger, wife of a client who wants to get rid of her husband and cash in on the fat life insurance policy. Huff falls hard and is drawn into the plot against his own better judgment and instinctual decency.

Cain loosely based the story on the real life wife-boyfriend-dead husband-insurance fraud case of Ruth Snyder, which he covered as a journalist in 1927.

The Big Sleep

Raymond Chandler

Knopf, 1939

The Big Sleep works as a crime novel even though the thing is a complicated mess, with loose ends, red herrings, and unresolved plot elements. Chandler himself was unable to sort it all out and explain major parts of it after its successful publication. Chandler often cobbled previously published short stories into a single novel, and The Big Sleep reworks two dissimilar tales, “Killer in the Rain" (1935) and "The Curtain" (1936).

When the book was turned into a film, director Howard Hawks asked the key question, “Who killed the chauffeur?”

Chandler replied “I have no idea.”

The Big Sleep introduces the iconic detective Phillip Marlowe, who is hired to track down the blackmailer of wealthy old man General Sternwood’s wild daughter, Carmen. Marlowe follows a trail of drugs, pornography, corpses and booksellers in an ever expanding plot line which, despite its many twists, is engrossing for the reader.